A rig drills for oil while pump jacks pull crude from the ground near Loco Hills in southeastern New Mexico. Most of the new oil investment in the state is coming from mid- and large-sized producers who can weather the price of $50 per barrel. Small, independent producers are having to hunker down until better times arrive. (Roberto E. Rosales/Albuquerque Journal)

Billions of dollars in new investment is flowing again in southeast New Mexico’s oil patch. Production is up, service companies are putting people back to work and more revenue is flowing into state coffers.

But by all accounts, it’s a modest recovery at best compared with the boom times of just a few years ago. Full recovery isn’t on the horizon yet. And, notwithstanding renewed confidence among producers, even the moderate gains achieved to date remain tenuous given the widespread uncertainty about oil prices going forward.

Many believe this is the new normal, at least for now, with most fresh investments coming from mid- and large-sized producers who have the cash to generate returns at $50 per barrel. Hundreds of others – small, independent producers who operate marginal stripper wells – are hunkering down to keep what they already have going until better times arrive

Crude price plunge

A truck delivers water for use in oil wells west of Hobbs. New Mexico’s oil output is at record highs. (Roberto E. Rosales/Albuquerque Journal)

Things are certainly better than they were in 2015 and early 2016, when world oversupply sent prices plummeting from historic highs of above $100 a barrel to below $30. That forced nearly all new exploration and drilling operations in New Mexico’s side of the Permian Basin to a screeching halt.

Active drilling rigs fell from about 100 before the crash to 15 by early last year. Between 12,000 and 18,000 workers lost their jobs, including both direct and indirect employment.

That, in turn, pushed the state budget into crisis, forcing lawmakers to cut spending by hundreds of millions of dollars in the last three years as revenue from taxes on oil production and related activities plunged.

But the price has since rebounded significantly, thanks largely to the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries’ decision last November to cut production by u

p to 1.8 million barrels per day. Prices for U.S. benchmark crude climbed above $50 per barrel earlier this year. It’s since fluctuated in the $45 to $50 range.

That, combined with new technological advances and operational improvements by companies to reduce costs, has allowed many mid- and large-sized producers to start drilling again for new oil. Particularly so in the Permian Basin, one of the country’s most-productive reservoirs, where operators use advanced techniques to crack open hard shale rock, releasing high-yield gushers that bring immediate returns on investment even at today’s moderate prices.

“The Permian’s geology makes it very attractive,” said New Mexico Oil and Gas Executive Director Ryan Flynn. “With all the technological advances, it’s a low-risk environment that’s made the whole area very resilient. Production there continues to increase.”

Unprecedented investment

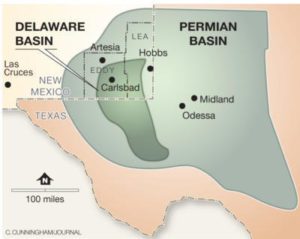

About 60 drilling rigs are now back at work in New Mexico, particularly in the Delaware Basin, an oval-shaped, shale-rock formation that protrudes from southwest Texas northward into Lea and Eddy counties. That zone’s lucrative potential is attracting unprecedented interest from some of the world’s largest producers, including ExxonMobil, which announced a $5.7 billion investment there early this year.

The Navajo Refining Co.

in Artesia. About 60 drilling rigs

are now back at work in

southeastern New Mexico,

particularly in the

Delaware Basin, an

oval-shaped, shale-rock formation that

protrudes from southwest Texas

northward into Lea and

Eddy counties. (Roberto

E. Rosales/Albuquerque Journal)

Since last September, mid- and large-sized companies have committed nearly $16 billion to investments in the Delaware to acquire lease holdings, initiate new drilling operations, and construct more pipelines and oil-and-gas gathering and processing infrastructure, said Daniel Fine, a longtime New Mexico-based energy analyst.

“There’s up to five layers in the Delaware that an operator can drill continuously through and claim all the reserves,” Fine said. “There’s a study underway by the U.S. Geological Survey that I expect will show up to 30 billion barrels of recoverable oil equivalent in the Delaware.”

That compares to 20 billion barrels the Geological Survey estimates for the neighboring Midland Basin in West Texas.

Increased activity is pushing New Mexico output to record highs. Average monthly oil production hit 13 million barrels a day from January through May, up from 12 million in 2016. Total output reached 65.5 million barrels in the first five months, up from 60.1 million in the same period last year.

That’s having an impact on jobs and state revenue. Unemployment in Lea County dropped from a high of 9.4 percent last October to 7.9 percent in July, according to the state Department of Workforce Solutions. And, rather than the chronic budget deficits faced in recent years, the state is expecting $25 million in new money for fiscal year 2019.

Looming oversupply

But that’s a far cry from the robust revenue streams before the oil crash, when both high production and record prices combined to fill state coffers. And unemployment in Lea County is still much higher than before the crisis.

“We’re getting some stability,” said Senate Finance Committee chair John Arthur Smith. “But it’s not a lot of additional revenue. Rather, we’re just not facing an emergency situation like before.”

Increased production improves things, but prices need to climb to the mid-$60s or beyond to significantly improve the budget, Smith said. For each $1 drop or increase, New Mexico loses or gains between $7 and $10 million.

But that’s unlikely in the short term. OPEC production limits are expected to end next March, and the U.S. Energy Information Administration projects domestic production will reach an all-time record of 10 million barrels a day in 2018, potentially creating another oversupply crisis and downward pressure on prices.

And in the meantime, even if prices remain stable at current levels, New Mexico’s small, independent producers are unlikely to initiate new production.

“Our company hasn’t drilled a new horizontal well this year, and we don’t plan on doing it,” said Raye Miller, president of Regeneration Energy Corp. in Artesia. “We just don’t see investment of new capital warranted at these price levels.”

By: Kevin Robinson-Avila (Albuquerque Journal)

Click here to view source article.

Commercial Association of REALTORS® - CARNM New Mexico

Breathing Easier In NM’s Oil Patch

08.28.2017

© 2024, Content: © 2021 Commercial Association of REALTORS® New Mexico. All rights reserved. Website by CARRISTO